The Biden Administration Suspends Asylum Agreements with the Northern Triangle

Secretary of State Antony Blinken recently announced that the United States has suspended and initiated the process to terminate asylum cooperative agreements with El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

Critics of the Trump Administration’s hardline immigration policies are looking to the Biden Administration to undo the massive changes to the U.S. immigration system adopted during the last four years, specifically with regard to asylum. While some have called upon the new administration to “swiftly undo the asylum overhauls,” it has largely indicated that it will proceed with caution, as a quick reversal to pre-Trump immigration policies might exacerbate an already dire humanitarian crisis and threaten regional stability.

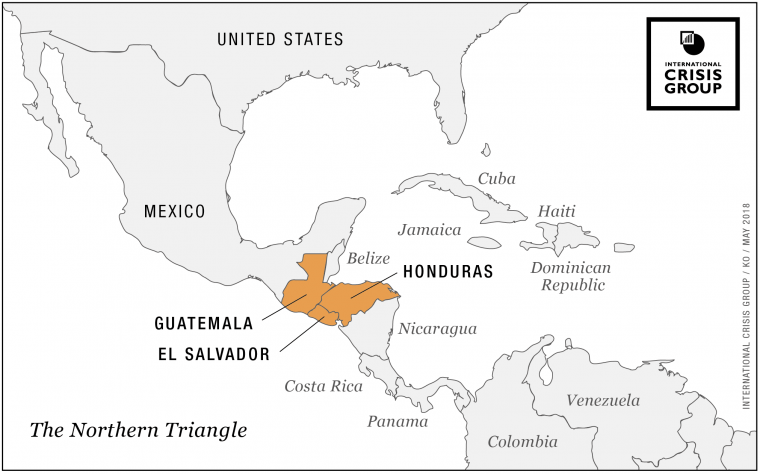

Nevertheless, the Biden Administration has also shown its willingness to act “swiftly.” For example, on February 6, the Biden administration announced that the United States had suspended and initiated the process to terminate three asylum cooperative agreements (ACAs) with El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras — countries collectively referred to as the “Northern Triangle.”

The Three Agreements

“Asylum Cooperative Agreements” are bilateral or multilateral agreements that seek to limit the use of signatory countries’ asylum systems by providing asylum seekers access to only one of the signatories’ systems. The purpose of the agreements is to share the burden of regional migration by transferring asylum seekers to countries designated as “safe” where they would be guaranteed access to full and fair examination of claims for international protection. As a result, under these three agreements negotiated by the Trump Administration, certain migrants arriving in the United States are removed to El Salvador, Guatemala, or Honduras to seek protection there instead.

What is the legal justification for such agreements? Even though persons physically present in the United States may typically apply for asylum under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), 8 U.S.C. § 1158(a)(1), Section § 208(a)(2)(A), 8 U.S.C. § 1158(a)(2)(A), provides that an alien covered by an asylum cooperative agreement — alternatively described as a “safe third country” agreement — is ineligible for applying for asylum in the United States so long as certain conditions are satisfied. That is, the alien will be ineligible “if the Attorney General determines that the person may be removed, pursuant to a bilateral or multilateral agreement, to a country (other than the country of the alien’s nationality) in which the alien’s life or freedom would not be threatened on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion, and where the alien would have access to a full and fair procedure for determining a claim to asylum or equivalent temporary protection.”

Until recently, the United States had only utilized the safe third country provision once. In 2002, the United States signed its first safe third country agreement with Canada, and the agreement was implemented in 2004. However, in the latter half of 2019, the United States signed three new ACAs with El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. On November 19, 2019, pursuant to the authority under Section 208(a)(2)(A) of the INA, the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issued a joint interim final rule (IFR) — titled “Implementing Bilateral and Multilateral Asylum Cooperative Agreements under the Immigration and Nationality Act” — authorizing the implementation of the ACAs between the United States and the countries of the Northern Triangle. 84 Fed. Reg. 63994. On December 29, 2020, DHS announced that all three agreements had entered into force.

Opposition to the Agreements

The new rule sparked political backlash. For example, a recent Democratic Staff Report prepared for the Committee on Foreign Relations argued that the United States’ Asylum Cooperative Agreements with El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras violate both the INA and the United States’ refoulement obligations under international law. One of the stated purposes of the ACAs is to enable countries with comparable asylum standards and procedures to transfer asylum seekers to countries designated as “safe” where they would be guaranteed access to full and fair examination of claims for international protection. However, since the implementation of the U.S.-Guatemala ACA over one year ago, not even one of the 945 asylum seekers transferred from the United States to Guatemala has been granted asylum. As a result, migrants turned away from the United States under an ACA are returned to one of the signatory countries where they are unable to seek protection. And while the ACA’s assume that El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras are “safe,” the report illustrates that once transferred to a signatory country, asylum-seekers ultimately abandon their claims to asylum.

Recent Court Challenges

The ACAs also drew opposition in U.S. courts, including a recent challenge in U.T. v. Barr. The federal lawsuit contends that the ACAs “unlawfully slam our nation’s door on people fleeing horrific violence and other forms of persecution by denying them the right to apply for asylum in the United States and shipping them to dangerous countries where there is virtually no chance they will find refuge.” Similar to what the Democratic Staff Report argues, the lawsuit argues that implementing the ACAs violates both domestic asylum laws and principles of international law.

With respect to domestic asylum law, the lawsuit asserts that the IFR violates § 1158(a)(2)(a)’s requirement that any receiving country must provide asylum seekers “access to full and fair procedures for determining their claims to asylum.” Citing high murder rates, rampant gender-based violence, and limited capacity to receive asylum, the lawsuit alleges that the countries of the Northern Triangle are not safe for asylum seekers and lack full and fair procedures.

Moreover, in 2017 and 2018, the Northern Triangle countries were three of the top four countries of origin for individuals granted asylum in the United States. As a result, the ACAs rendered the countries generating the largest number of refugees as the location where asylum seekers would be forced to seek protection. These factors cast serious doubt on the claim that the parties to the ACAs are “safe third countries” that provide asylum seekers with access to full and fair proceedings.

And with respect to international law, the lawsuit criticizes the United States’ failure to uphold its non-refoulement obligations enshrined in Article 33 of the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees. The principle of non-refoulement prohibits countries from forcibly expelling or returning a refugee to a country or territory where she would face torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment and other irreparable harm. Arguing that the IFR imposes procedures that inadequately protect asylum seekers, the complaint in Barr asserts that the ACAs contravene these international legal obligations.

The Future of ACAs Going Forward

Despite the opposition to these three ACAs in particular, proponents still argue that ACAs can promote regional stability, reduce the burden on the system, limit the number of applicants, and promote a cooperative approach to controlling regional migration. Again, the stated purpose of the three Trump-era agreements was to provide a mechanism for strengthening the overall asylum capabilities in the Northern Triangle countries and across the region by allowing asylum seekers to access protection closer to their home, thus enhancing regional stability. The administration further supported its position by explaining that the agreements serve an important foreign policy goal by reaffirming the commitment of the United States and the Northern Triangle countries to combatting mutual threats, including transnational criminal organizations and gangs, migrant smuggling, drug trafficking, and human trafficking.

Even though the Biden administration suspended the Trump-era ACAs and has initiated the process to terminate them, the press release announcing the United States’ withdrawal from the agreements still stated that the United States “is taking this action as an effort to establish a cooperative, mutually respectful approach to managing migration across the region.” In fact, it claims that the decision to suspend the ACAs is part of the “first concrete steps on the path to greater partnership and collaboration in the region.”

While the new administration believes there are “more suitable ways to work with our partner governments to manage migration across the region” than with these particular ACAs, it remains to be seen whether the Biden Administration will negotiate new ACAs in the future as part of its plan to address these issues. Given the tensions between the focus on regional stability and humanitarian concerns, the Biden administration will need to cautiously devise a strategy on how to best balance the nation’s strategic interests with democratic values and respect for human rights.

Morgan Kaplan is a second-year student at Columbia Law School and a Staff member of the Columbia Journal of Transnational Law. She graduated from Georgetown University in 2018.